Author’s Note: When I first started writing this piece, I wanted to talk about my experience of touring the Stasi Secret Prison (Gedenkstätte Berlin-Hohenschönhausen), and how as Americans, we must be vigilant against committing similar human rights violations (such as CIA torture, and NSA domestic spying). Then The Guardian released an article about the Chicago Police Department’s secret prison, and I felt the need to rewrite the piece to address this latest development. The more I researched the justice system in America, the more appalling it became. Like most Americans (and a great deal of non-Americans), I want to believe my native country is a land of opportunity, social mobility, and justice. This is our ideal, but we are far from it at the moment.

I know this will come off as some ultra-liberal howling to the moon about social and racial injustice in America. And I know many will scoff at my unfavorable comparisons to the horrible Stalinist regimes of the past. However, I think conservatives and liberals should be able to agree in the basic principles enumerated in our Bill of Rights. Due process, proper search and seizure, the right to a lawyer, and equal treatment under the law are values that are held by all Americans, red, blue, or somewhere in between (and a great deal outside, as well). The political divide seems worse now than ever before, but we must work together to make sure that these enshrined values are upheld across the U.S. for all Americans.

* * *

The tour proceeded slowly through the basement corridor of the former Stasi secret prison. These interior walls hadn’t seen natural light since its construction many decades ago, and yet a bright and clear light was shining on a very modern problem, one that threatens dictatorships and democracies alike. All nations carry baggage, and histories that are rife with human rights abuses and questionable moral judgments. How we live up to our ideals echo with a far louder reverberation than the sounds carried through the confined basement.

Communism, at least the Stalinist variety practiced by the former Eastern Bloc countries and North Korea, holds a certain fascination for me. Unlike terrible regimes in the past, this special brand of totalitarianism was wide-spread during my lifetime, and sadly still persists today in East Asia. In this last holdout from the Cold War, I watched the lights extinguished on a nightly basis, knowing that the regime was inflicting immeasurable suffering just beyond the bucolic rolling hills on the horizon. I, like 50 million more, was safe across the border in South Korea. Many turn a blind eye, but even those who do not were subjected to the knowledge that there is little that can be done to help.

It is easy, perhaps, to put one miserable country out of your mind, but this was not the case a quarter of a century ago when Central and Eastern Europe were under Soviet control. And nowhere on the continent was this control more necessary than in the divided city of Berlin. The Berlin Wall was the most iconic symbol of this division, but the “Anti-Fascist Barrier” (as the East Germans would have called it) was nothing compared to the daily control and mutual distrust fostered by the German Democratic Republic. A better symbol would have been the secret prison kept by the secret state police, the Stasi.

It would have been, had the general population even known of its existence. When East Germans stormed Stasi headquarters in 1990, it was a jubilant moment, but this prison remained untouched. No one knew where it was. Despite its location well within the city’s confines, it appeared on no maps. Its prisoners were brought here in secrecy, and its guards went through great lengths to keep the prisoners in the dark about its size and location. The “suspects,”–if such a term can be applied to those with presumed guilt–would be brought in an unmarked, windowless van. Their days of contact with the natural world were over. Their life now would consist of nothing but absolute control, including the way they slept at night. Their only human contact would be with their interrogator, a move consciously made to cultivate Stockholm Syndrome, and make it more likely for the prisoner to talk.

Deep inside, most people hold the belief that they could withstand wrongful prosecution and interrogation. Our guide did well to dispel us of that notion. Everyone, guilty or innocent, confessed. It was just a matter of time. The interrogators were all trained psychologists, and their methods were as diverse as they were terrifying. Perhaps they would take their time, asking the same question over and over for hours on end, until the prisoner would have an emotional break-down and say whatever they wanted to hear. At the beginning of the tour, we watched actual video of this technique being used. The woman being questioned broke down and said through her heavy sobs, “Just tell me what you want to hear?” The interrogator, not finished with his game, replied, “You know what I want to hear. What do I want to hear?”

Perhaps they would throw the prisoner in a cell barefoot with standing water and leave them there until they talked (it doesn’t sound so bad, but it will cause great discomfort and eventually kidney failure). Perhaps they would throw you in a standing cell, in a space so small that you cannot sit, and then close the door so it is air-tight, slowly asphyxiating the prisoner until he’s ready to talk or sign a blank piece of paper. And yes, they used waterboarding as well. One thing was clear, regardless of innocence or guilt, everyone confessed.

Now, the prison is a terrifying tourist attraction, but one well worth the visit. And sadly, one does not need to look far to see similar human rights abuses in the U.S., especially in the post-9/11 world.

Just this week, The Guardian reported on a secret interrogation facility used by the Chicago Police Department. According to the piece:

Unlike a precinct, no one taken to Homan Square is said to be booked. Witnesses, suspects or other Chicagoans who end up inside do not appear to have a public, searchable record entered into a database indicating where they are, as happens when someone is booked at a precinct. Lawyers and relatives insist there is no way of finding their whereabouts. Those lawyers who have attempted to gain access to Homan Square are most often turned away, even as their clients remain in custody inside.

This is just one example of one high-profile police department. How many other similar facilities exist? And how often are American citizens held without access to a lawyer, without being read their Miranda rights, without due process, and without protection from cruel and unusual punishment? Of course, this is wild speculation, but this facility has allegedly been operating since the 1990’s, and this report is only now coming to light.

How many Americans are in prison right now from false confessions? As we saw in Berlin, most people, regardless of their innocence, will eventually confess. According to this New York Times piece, false confessions do happen in America:

Eddie Lowery lost 10 years of his life for a crime he did not commit. There was no physical evidence at his trial for rape, but one overwhelming factor put him away: he confessed.

…But that vindication would come only years after Mr. Lowery had served his sentence and was paroled in 1991.

“I beat myself up a lot” about having confessed, Mr. Lowery said in a recent interview. “I thought I was the only dummy who did that.”

But more than 40 others have given confessions since 1976 that DNA evidence later showed were false, according to records compiled by Brandon L. Garrett, a professor at the University of Virginia School of Law. Experts have long known that some kinds of people — including the mentally impaired, the mentally ill, the young and the easily led — are the likeliest to be induced to confess. There are also people like Mr. Lowery, who says he was just pressed beyond endurance by persistent interrogators.

Forty might seem like a low number, but think about the number of cases where DNA samples were not (or could not be) collected. And these are just false confessions which were eventually overturned. I think we can reasonably assume that there are far more people currently sitting in prison for crimes they didn’t commit, than there have been released after a false confession. Of course mistakes will be made, but when we imprison such a large portion of our population, mistakes will happen with more regularity.

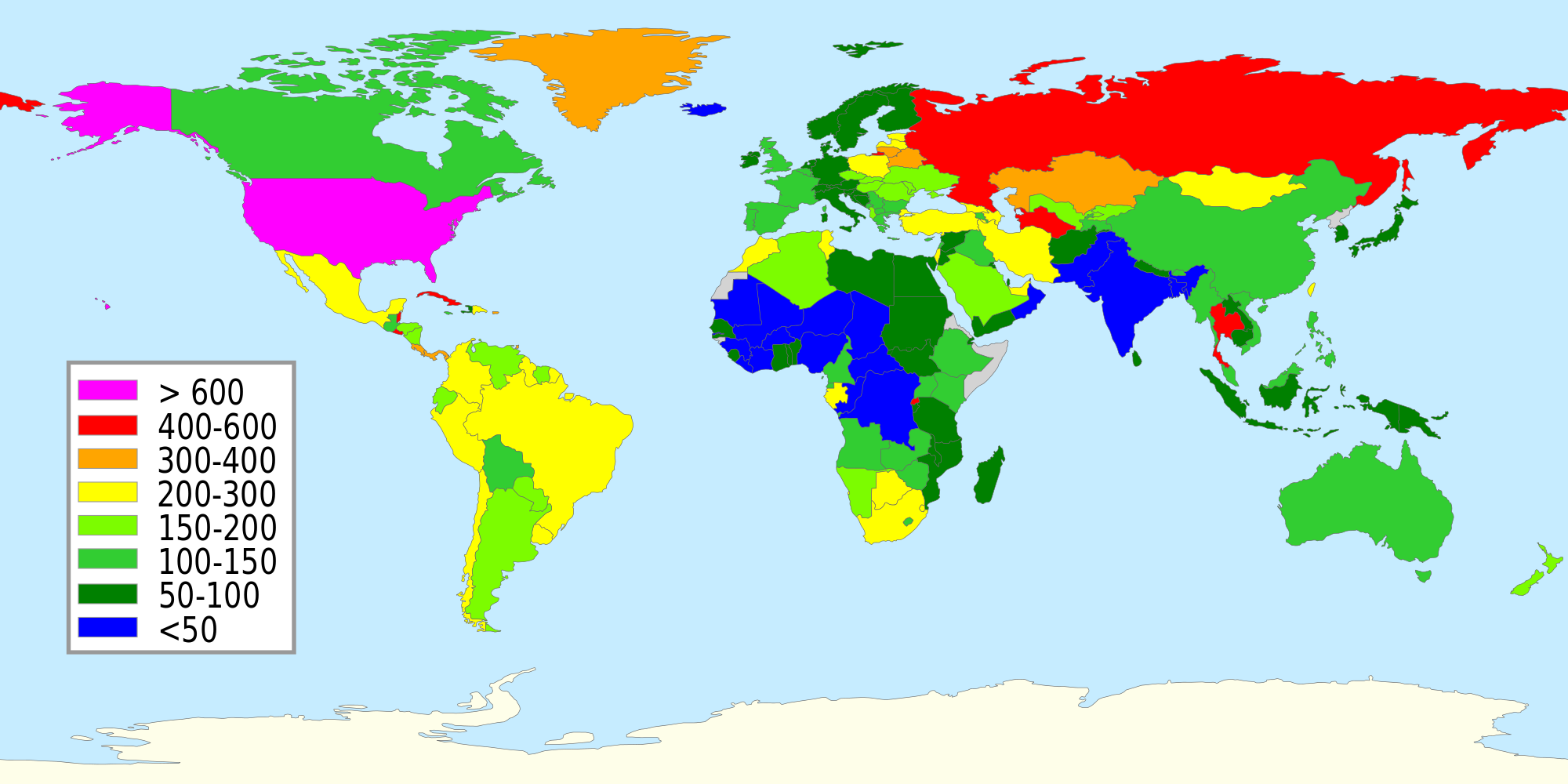

By any reasonable measure our incarceration rate is sickeningly high. In fact, it’s one of the highest. We have over 700 prisoners for every 100,000 people. If we formed a city of just people incarcerated in America right now, it would be the fourth largest in the U.S. If we formed a city out of everyone who saw the inside of a jail cell this year, it would be as big as New York and LA combined.

How does this rank with the rest of the world? Out of 222 countries that we have known incarceration rates for, we’re second only to the Seychelles (868 per 100,000), and have rates roughly the same as North Korea (best estimate is between 600-800 per 100,000). Other notables: #7 Cuba (510), #10 Russia (467), #34 South Africa and Iran (290), #81 Saudi Arabia (161), #98 England and Wales (148), #123 China (124, best estimate), #149 South Korea (98), #167 German (76), #179 Denmark (67), #198 Japan (50).

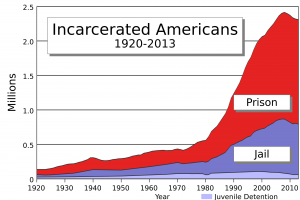

These numbers do not shine a favorable light on the American justice system. Since 1980, the incarceration rate has sky-rocketed in the U.S., despite the crime rate steadily decreasing since the early 90s. From 1980-2008 the number of prisoners more than quadrupled, and only during the Obama administration have we seen the numbers take a very modest decline.

Business is booming! The incarceration rate has more than quadrupled in America since 1980, despite a decrease in crime. Source: Wikipedia.

A great deal of these arrests have occurred as a direct result of the “War on Drugs” which has been effective at swelling our prison population with non-violent offenders. From 2001-2010, a staggering 8.2 million people were arrested for marijuana, 90% of those arrests being for simple possession (i.e. without the intent to sell). With politicians and judges wanting to seem “tough on crime” many of these arrests face lengthy minimum sentences. An extreme example of this is the roughly 3,000 prisoners currently sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole for non-violent crimes.

Further, there’s a terrible racial injustice that comes with these statistics, as blacks and Latinos are much more likely to be arrested and face worse charges than their white counterparts. Despite violent crime rates declining in the black community, the incarceration rate has doubled since the 1970’s, and is five times the rate for whites. Despite the rates for selling and using drugs being equal across the racial divide, blacks remain 3.6 times as likely to be arrested for selling, and 2.5 times as likely to be arrested for possessing drugs.

All of this leads to devastating long-term knock-on effects. After serving time in prison, convicts must report the information on any future job application–thus reducing the likelihood of employment–and in most states they lose their voting rights–thus reducing their ability to change an unjust system. In fact, nearly 6 million citizens were banned from voting in the 2012 election because of a prior conviction. The rapid rise in incarceration rates in America has coincided with reduced social mobility for all races, and social scientists have a reason to believe the two are causally linked.

I, like most Americans, want to believe my country to be a shining example for the rest of the world. I want us to not just say we’re better, but to actually be better. I want equal opportunities for all, regardless of race, religion (or lack thereof), gender, sexual orientation, or social background. I want to think of America as a place where freedom and justice reigns. And yet, we have produced a paranoid, scared, rabidly unsympathetic society, more willing to lock away its problems than to confront and fix them. We espouse freedom, and yet take freedom away from a larger percentage of our population than just about anywhere else on the globe.

This piece merely scratches the surface of some of the inequities and failures of our so-called justice system. Since Obama took office in 2009, we have seen a slight dip in the incarceration rate, and I hope this is a trend we see continue after nearly three decades of uninterrupted growth. Ending the War on Drugs would be a major step in accomplishing this feat, as would decriminalizing or legalizing other non-violent offenses.

Looking into the past can act as a mirror, reflecting the parallels to modern society in terrifying clarity. This is a comparison I never wanted to make, and I dearly hope that it doesn’t take a revolution to force us to change our ways. We should and can do better.

1 comment for “Liberty and Justice for All?”